The Miracle of the Eye

Charles Darwin described the eye as one of the greatest challenges to his theory. How could he explain it? The eye, after all, is simply incompatible with evolution. "To suppose," he admitted, "that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances . . . could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree" (The Origin of Species, 1859, Masterpieces of Science Edition, 1958, p. 146).

Jesus said that "the lamp of the body is the eye" (Matthew 6:22).

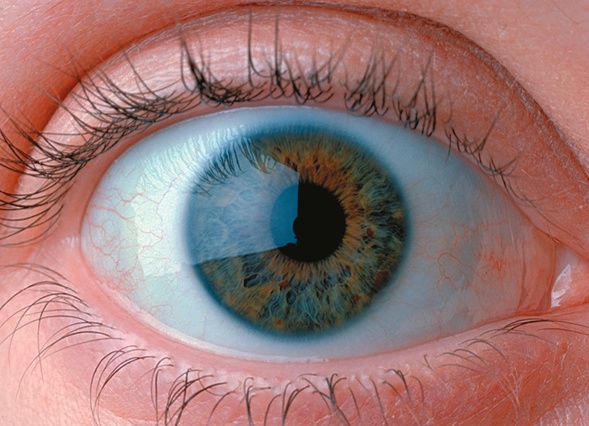

The human eye possesses 130 million light-sensitive rods and cones that convert light into chemical impulses. These signals travel at a rate of a billion per second to the brain.

The essential problem for Darwinists is how so many intricate components could have independently evolved to work together perfectly when, if a single component didn't function perfectly, nothing would work at all.

Think about it. Partial transitional structures are no aid to a creature's survival and may even be a hindrance. If they are a hindrance, no further gradual development would occur because the creature would, according to advocates of natural selection, be less apt to survive than the other creatures around him. What good is half a wing or an eye without a retina? Consequently, either such structures as feathered wings must have appeared all at once, either by absurdly implausible massive mutations ("hopeful monsters," as scientists refer to such hypothetical creatures) or by creation.

"Now it is quite evident," says Francis Hitching, "that if the slightest thing goes wrong en route—if the cornea is fuzzy, or the pupil fails to dilate, or the lens becomes opaque, or the focusing goes wrong—then a recognizable image is not formed. The eye either functions as a whole, or not at all.

"So how did it come to evolve by slow, steady, infinitesimally small Darwinian improvements? Is it really possible that thousands upon thousands of lucky chance mutations happened coincidentally so that the lens and the retina, which cannot work without each other, evolved in synchrony? What survival value can there be in an eye that doesn't see?

"Small wonder that it troubled Darwin. 'To this day the eye makes me shudder,' [Darwin] wrote to his botanist friend Asa Gray in February, 1860" (The Neck of the Giraffe, 1982, p. 86).

Incredible as the eye is, consider that we have not one but two of them. This matched pair, coupled with an interpretive center in the brain, allows us to determine distances to the objects we see. Our eyes also have the ability to focus automatically by elongating or compressing themselves. They are also inset beneath a bony brow that, along with automatic shutters in the form of eyelids, provide protection for these intricate and delicate organs.

Darwin should have considered two passages in the Bible. "The hearing ear and the seeing eye, the Lord has made them both," wrote King Solomon (Proverbs 20:12). And Psalm 94:9 asks: "He who planted the ear, shall He not hear? He who formed the eye, shall He not see?"

The same can be said of the brain, nose, palate and dozens of other complex and highly developed organs in any human being or animal. It would take a quantum leap of faith to think all this just evolved. Yet that is commonly taught and accepted.

After reviewing the improbability of such organs arising in nature from an evolutionary process, Professor H.S. Lipson, a member of the British Institute of Physics, wrote in 1980: "We must go further than this and admit that the only acceptable explanation is creation. I know that this is anathema to physicists, as indeed it is to me, but we must not reject a theory that we do not like if the experimental evidence supports it" (Physics Bulletin, Vol. 30, p. 140).