Ossuary verdict

Experts testify to its authenticity

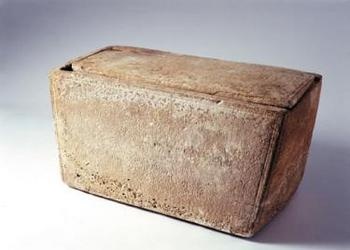

The implications of the find, soon known as the James ossuary, were enormous—if authentic, the first-century artifact might well be the earliest known archaeological evidence yet discovered referring to Jesus of Nazareth.

Although the names "James," "Joseph" and "Jesus" were fairly common in the first century and have been found individually on a number of such bone boxes, these names being spelled out together in the same exact familial relationship given in the Gospels makes it virtually certain that the complete inscription refers to those mentioned in the Gospels.

While it's fairly common for such Aramaic inscriptions to mention the name of one's father, mention of one's brother is very rare—found in only one other case, and only where the brother was notable or widely recognized. Thus the probability that this inscription refers to Jesus of Nazareth seems conclusive.

The ossuary's existence was first announced at an Oct. 21, 2002, press conference in Washington, D.C., held by the Biblical Archaeology Society and the Discovery Channel. This was followed shortly by a detailed article in Biblical Archaeology Review magazine by André Lemaire, an expert in ancient Middle Eastern inscriptions and chairman of the Hebrew and Aramaic philology and epigraphy section at the Sorbonne in Paris, who had translated the lettering on the artifact.

By its very nature the bone box could be dated to around Christ's time since such ossuaries were used only from about 20 B.C. up to the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in A.D. 70. According to Jewish custom at the time, bodies were first sealed in caves or tombs, and after decomposition the bones were transferred to these carved stone boxes—sometimes bearing an inscription identifying whose bones were inside, but often not.

Before the discovery was made public, Hershel Shanks, editor of Biblical Archaeology Review, had the James ossuary examined by lab experts from the Geological Survey of Israel (GSI) to ensure that it was genuine and not a modern forgery.

As with other artifacts of this sort, the ossuary was covered with a thin coating of mineral accumulation called a patina, which develops on stone over centuries. A modern forgery would lack such a coating, or show evidence that it had been artificially created and applied, and would likely show modern tool marks.

After examining the ossuary microscopically, the GSI scientists concluded in their report published in Biblical Archaeology Review that "the patina does not contain any modern elements (such as modern pigments) and it adheres firmly to the stone. No signs of the use of a modern tool or instrument was [sic] found. No evidence that might detract from the authenticity of the patina and the inscription was found."

In addition to Professor Lemaire, Shanks also had the inscription examined by Professor Joseph Fitzmyer, an expert on the first-century Aramaic language and a preeminent Dead Sea Scrolls scholar. Both concluded the inscription was genuine.

Shortly afterward, the ossuary was shipped to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, where it was exhibited and examined by a different panel of experts who also concluded it was authentic.

However, because the ossuary had been removed from its ancient burial spot and purchased from an Arab antiquities dealer rather than having been found in a professionally supervised archaeological excavation, concerns remained about its authenticity.

Rumors began to spread that, although the ossuary itself was a genuine first-century artifact and the words "James, son of Joseph" were authentic, a forger had added "brother of Jesus" to the end of the inscription in hopes of drastically increasing its value by associating it with the Jesus Christ of the Bible.

Rumors also circulated that inscriptions on a prized artifact in the Israel Museum, as well as on a recently discovered plaque thought to describe repairs to the ancient Jerusalem temple constructed by the biblical King Solomon, were also modern forgeries.

In 2003 the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) announced its conclusion that the inscriptions had been faked. And in December 2004 Oded Golan, an Israeli collector of biblical-era artifacts and owner of the James ossuary, was charged with heading a forgery ring responsible for the artifacts in question.

Then, with a flurry of headlines denouncing it as a fake, the ossuary disappeared from public view, and an excruciatingly long court trial began.

In Israel, trials are not decided by jury but by a single judge. Due to the complexity of the issues involved, the case was given to a judge with a degree in archaeology. Few anticipated that the trial would last more than five years, involve 138 witnesses and produce 12,000 pages of court transcripts. When the case ruling was handed down on March 14, 2012, it was 474 pages long.

The judge cleared all defendants of charges of forgery. Although he didn't rule on the authenticity of the artifacts themselves, it was evident that the Israel Antiquities Authority had overplayed its hand.

In spite of enormous expense and effort, the IAA was unable to prove any of its allegations of forgery. Every allegation of the artifacts' inscriptions being forged was countered by expert witnesses from a number of scientific fields testifying to their apparent authenticity.

At one point even the lead IAA archaeologist spearheading the accusations of forgery was forced to admit on the witness stand that the ancient patina covering the James ossuary extended into parts of the letters of the words "brother of Jesus"—the very part of the inscription alleged to have been forged in modern times.

So where does that leave us?

As is the case with any artifact not uncovered in a scientifically controlled excavation, we will never be able to prove with 100 percent certainty that an artifact is genuine. But the number of experts who have testified about the James ossuary, and their impeccable credentials, should certainly give critics pause.

In any case, the finding of ancient artifacts has added much to the list of "infallible proofs" (Acts 1:3) regarding the authenticity of the biblical record. We can choose whether we accept the evidence or not. The Good News will continue to report on discoveries relating to the Bible so you can judge for yourself. As a starter, request or download your free copy of Is the Bible True? It's an important first step in addressing these issues in your mind.