The Exodus Plagues: Judgment on Egypt’s Gods

In the story of Israel’s Exodus from slavery in Egypt, God sent devastating plagues on the Egyptians. And there’s much more to these plagues than you probably realize!

Many of us are probably familiar with the basics of the story of ancient Israel’s Exodus from enslavement in Egypt. To briefly recap, the Israelites migrated to Egypt in the time of Joseph, 17 years before the death of the patriarch Jacob, whom God had renamed Israel. Initially they enjoyed the favor of the Egyptians because of all that Joseph had done as the pharaoh’s vizier or prime minister. But as the years passed, that relationship changed. The Egyptians came to view the Israelites as a threat.

In time a new pharaoh came to power who enslaved the Israelites. Conditions grew so bad that the Egyptians began killing Hebrew male babies to prevent the Israelites from outnumbering the Egyptians.

During this time God raised up a deliverer named Moses. He was saved at birth and grew up as a member of the Egyptian royal family. But after killing an Egyptian, he fled from Egypt to the land of Midian, where, 40 years later, God spoke to him at the burning bush and sent him back to Egypt to deliver the Israelites from slavery.

In Exodus 7:1-5 God told Moses that He would do three things:

1. He would bring the Israelites out of Egypt,

2. He would do it “by great judgments,” and

3. He would do it in a way that “the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord”—the true God.

In Exodus 12:12 God adds that He was doing something else very important: “Against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgment.” So the judgments God would carry out would be, on a certain level, against the Egyptian gods. In doing this He would teach a lesson to both the Egyptians and the Israelites, who by now had been in Egypt for a number of generations and had drifted far from the religion of their forefathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. They had become thoroughly immersed in a corrupt Egyptian culture and religion.

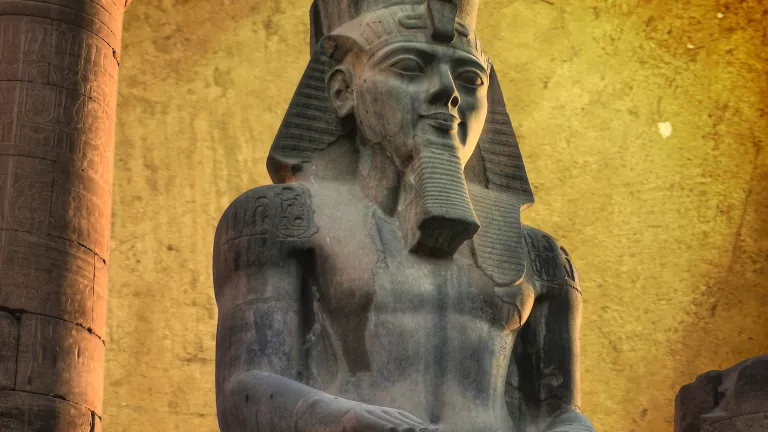

Egyptian culture was very idolatrous, with a multitude of gods and goddesses. Many of these were assumed to take the form of animals, so the Egyptians considered bulls, cows, rams, cats, crocodiles, cobras, frogs and various insects and birds sacred. Note some of these creatures in the depictions of Egyptian deities accompanying this article.

Each of the plagues God sent was a direct challenge to one or more of the gods and goddesses of Egypt. And while the Egyptians would’ve seen such things as locusts and biting insects before, what made these plagues unique is that God divinely intensified these plagues and brought them on the Egyptians at a time of His choosing.So the plagues were much worse than they normally would’ve been, and they came exactly when God through Moses said they would happen to show that God was the one behind them.

So let’s notice each plague and then see some of the gods or goddesses the true God was executing judgment against. We’ll see what the true God did to teach a lesson to both the Egyptians and the Israelites.

The first plague—waters turn to blood

The first plague was directed against the Nile River, the life and heart of Egypt. Egypt was a desert country, and its economy and livelihood depended on the Nile. Its crops were irrigated by the Nile, and its fields depended on fertile soil washed in by the river. The Nile was also the primary“highway” for the country—much of its trade and commerce depended on it.

So what happened to this lifeblood of the nation? Let’s read about it in Exodus 7:19-20: “Then the Lord spoke to Moses, ‘Say to Aaron [Moses’ brother who accompanied him], “Take your rod and stretch out your hand over the waters of Egypt, over their streams, over their rivers, over their ponds, and over all their pools of water, that they may become blood. And there shall be blood throughout all the land of Egypt, both in buckets of wood and pitchers of stone.”’

“And Moses and Aaron did so, just as the Lord commanded. So he lifted up the rod and struck the waters that were in the river, in the sight of Pharaoh and in the sight of his servants. And all the waters that were in the river were turned to blood” (emphasis added throughout).

While this plague was primarily directed against the Nile River, it went beyond that. All other water sources were affected, including irrigation streams and pools and even water stored in pitchers and buckets in people’s houses.

This was a terrible disaster for the Egyptians. The whole lifeblood of the country was poisoned and undrinkable. And if that weren’t bad enough, “the fish that were in the river died, the river stank, and the Egyptians could not drink the water of the river. So there was blood throughout all the land of Egypt” (Exodus 7:21).

This was a complete catastrophe. The Egyptians’ supply of water for drinking, bathing and washing was now a toxic mess. The fish, one of their major food sources, were wiped out. This was utterly devastating to the country.

So how was this a judgment against the Egyptian gods? Because the Nile was so important to the Egyptians, they worshipped several gods who were responsible for watching over it. The great god Khnum, usually represented as a human male with a ram’s head, was viewed as the giver and guardian of the Nile River.

Another god, Hapi, spirit of the Nile, was credited with the annual Nile flood that brought in thousands of tons of fresh topsoil to refertilize the land every year. He was also honored as god of fishes, birds and marshes, which is why he was often depicted with marsh plants on his head. Also linked to the Nile floodwaters were the gods Sodpet and Satet.

One of Egypt’s trinity of greatest gods was Osiris, god of the underworld. The Egyptians viewed the Nile River as his bloodstream—and now it was literally like blood! You can imagine the horror and feelings of abandonment of the Egyptians as they looked on the formerly beautiful, powerful and life-sustaining river that was now a giant stinking cesspool with tons of dead and rotting fish lining the shores. This struck also at Hatmehit, guardian goddess of fish and fishermen.

These great gods of Egypt proved powerless to prevent this great plague on the Nile. They were shown to be nothing compared to the God of Israel!

A God of judgment

Why did God start with a plague on the Nile? And why did He choose a plague of blood? It’s because He is a God of judgment and justice.

The Egyptians took thousands of tiny helpless Israelite babies and tossed them into the Nile to drown or to feed the crocodiles and fish (Exodus 1:22). The Egyptians had sought the blood of the Hebrews, and God essentially responded, “If you want blood, I’ll give you blood to drink.”

That’s why God chose the Nile, and that’s why He chose to turn it to blood—because He’s a God of judgment and justice. We see an important lesson in this. God may delay His judgment, but there comes a time when He delays no more. And when He decides it’s time to exact justice, vengeance is His.

Because the Egyptians had shown no mercy in brutally enslaving and oppressing the Israelites, and attempting genocide against them, God brought severe judgment on Egypt and its false gods.

The second plague—frogs

The next plague was that of frogs, described in the first part of Exodus 8. Large numbers of frogs would not have been unusual, because the Nile had plenty of marshes that were a natural breeding ground for frogs. But this plague was different.

“And the Lord spoke to Moses, ‘Go to Pharaoh and say to him, “Thus says the Lord: ‘Let My people go, that they may serve Me. But if you refuse to let them go, behold, I will smite all your territory with frogs. So the river shall bring forth frogs abundantly, which shall go up and come into your house, into your bedroom, on your bed, into the houses of your servants, on your people, into your ovens, and into your kneading bowls’”’” (Exodus 8:1-3).

Frogs were considered a manifestation of the goddess Heqet, goddess of birth and wife of the creator of the world. Heqet was depicted with the head of a frog and the body of a woman. Also, the court of Hapi, mentioned above, included crocodile gods and frog goddesses. And the primordial gods Nun, Kek and Heh were each depicted as a man with a frog’s head.

Frogs were viewed as sacred in Egypt because they lived in two worlds—in water and on land. They were considered so sacred that even accidentally stepping on one could be punished by death.

Notice two great ironies here. Heqet was supposed to be the goddess who controls birth, but in this plague literally millions and millions of frogs were overflowing the land—the frog birth rate was obviously out of control! And accidentally killing one by stepping on it was punishable by death, yet how could that be avoided when the ground was everywhere covered with a slimy, croaking mass of frogs? There were frogs on the ground, frogs in the houses, frogs in their beds, frogs in their cooking ovens and frogs in their bowls.

The Egyptians literally could not walk without stepping on frogs and squashing them. But in so doing they were violating their own laws and sentencing themselves to death for offending the goddess Heqet and these other frog deities! Finally the people had to go out to gather them into great mounds of decaying, stinking frogs—so much for their sacred animal! Here God showed that He was far more powerful than all these so-called gods!

The third plague—lice

The third plague, lice, is found in Exodus 8:16-17: “So the Lord said to Moses, ‘Say to Aaron, “Stretch out your rod, and strike the dust of the land, so that it may become lice throughout all the land of Egypt.”’ And they did so. For Aaron stretched out his hand with his rod and struck the dust of the earth, and it became lice on man and beast. All the dust of the land became lice throughout all the land of Egypt.”

Which god of Egypt was now being judged? This plague was perhaps directed in some measure at Geb, the god of the earth. Egyptians gave offerings to Geb for the bounty of the land—but in this case, rather than the land bringing forth crops and fruit and vegetables, it brought forth itching, biting lice. And their god Geb was shown to be powerless to prevent it!

This infestation can also be seen as a slap at the Egyptian gods in general, as they were unable to withstand it. Egyptians invoked Har-pa-khered (Horus in child form) to ward off dangerous creatures and Imhotep as god of medicinal healing as well as other healing gods, but there was no relief. Pharaoh too was considered a god, as we will consider more later, yet he was personally afflicted with the lice.

It’s interesting too how this affected the priests of the gods of Egypt. The Greek historian Herodotus, who traveled to ancient Egypt, tells us that the Egyptian priests had to perform many cleanliness rituals to serve in their role as priests. Some of these were specifically to avoid being infected with lice, which would prevent them from carrying out their religious duties in service to their gods.

But now the presence of these lice meant that the Egyptian priests could no longer serve their gods. They couldn’t even go into the temples to lead the worship of the Egyptian gods because they were now considered unsuitable to perform their rituals! So this was a blow not only against Geb and the other Egyptian gods, but also against all the pagan priests of Egypt. Again, God was showing them exactly who is really in charge!

Again we see irony in this plague. The land was infected with lice, making every person and animal miserable, but the priests of Egypt could not even enter their temples to pray to their gods due to them now being unsuited to serve because of lice!

The fourth plague—swarms

On the surface, the next plague sounds a lot like the plague of lice. But it was probably quite a bit different, as we will see.

Exodus 8:20-23 states: “And the Lord said to Moses, ‘Rise early in the morning and stand before Pharaoh as he comes out to the water. Then say to him, “Thus says the Lord: ‘Let My people go, that they may serve Me. Or else, if you will not let My people go, behold, I will send swarms of flies on you and your servants, on your people and into your houses. The houses of the Egyptians shall be full of swarms of flies, and also the ground on which they stand.

“And in that day I will set apart the land of Goshen, in which My people dwell, that no swarms of flies shall be there, in order that you may know that I am the Lord in the midst of the land. I will make a difference between My people and your people. Tomorrow this sign shall be.’”’”

The phrase “of flies” here was added by translators and isn’t in the original Hebrew, which simply uses the word “swarms” in reference to buzzing, flying insects.

A most likely scenario, based on the way we’ve seen God operate so far in this story, is that the “swarms” in this passage were swarms of another flying and crawling insect that the Egyptians considered holy—the scarab beetle. These were actually dung beetles—insects that feed on manure! Scarab beetles could also be very destructive, because they had mandibles that could saw through wood.

If this is the case, was this plague directed at a particular god of Egypt? Yes it was. The Egyptian god Kheper was depicted as a man with a dung beetle in place of his head. Kheper was viewed as the god who pushed the sun across the sky. He was associated with the dung beetle because dung beetles would roll manure into spherical balls and push these around on the ground, similar to how the Egyptians thought Kheper pushed the sun across the sky.

The Egyptians also considered the scarab beetles as divine since they emerged from dead animals or manure and thus were viewed as being created from dead matter. Because of this they came to be associated with rebirth and resurrection.

The Egyptians apparently didn’t realize that the beetles simply laid their eggs in dead animals or manure, and they hatched out later. It certainly had nothing to do with being divine!

So when this swarm of creatures invaded the land and got into everything like the earlier plagues of lice and frogs, this was a direct affront to the god Kheper. Kheper was shown to be incapable of controlling the highly destructive insects that were now chewing their way through the Egyptian houses and buildings. We might also note the supreme god Amun, god of the wind, who should have been able to blow the swarms away. The true God here showed yet more Egyptian gods to be utterly powerless.

Note also that this is the first plague in which God made a distinction between His people and the Egyptians. The Israelites suffered the previous plagues alongside the Egyptians. But now God kept this and the remaining plagues away from Goshen, where His people lived.

The fifth plague—disease on livestock

The fifth plague, beginning in Exodus 9:1, was directed against domestic animals: “Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘Go in to Pharaoh and tell him, “Thus says the Lord God of the Hebrews: ‘Let My people go, that they may serve Me.

“For if you refuse to let them go, and still hold them, behold, the hand of the Lord will be on your cattle in the field, on the horses, on the donkeys, on the camels, on the oxen, and on the sheep—a very severe pestilence. And the Lord will make a difference between the livestock of Israel and the livestock of Egypt. So nothing shall die of all that belongs to the children of Israel’”’” (Exodus 9:1-4).

This plague created an enormous economic disaster for the Egyptians. It affected their food, transportation, military capability, farming capacity and economic goods that were produced by these livestock. But still Pharaoh’s heart remained hardened.

Cattle in Egypt were not just highly valued, they were also considered sacred. The Egyptians worshipped many animals, and among them were bulls and heifers. The creation god Ptah was represented by a living bull known as the Apis bull. The Apis bull was very sacred, and when it died the Egyptians mourned as though they had lost a pharaoh. After death, the Apis bull was embalmed and placed in a tomb like a pharaoh.

The creator sun gods Atum and Re, blended as the same deity, were represented by the black bull Mer-wer or Nem-wer (called by the Greeks Mnevis). Sky and creation goddesses Nut and Neith were depicted as a celestial cow giving birth to the universe and other gods.

One of Egypt’s greatest mother goddesses was Hathor, depicted as a cow-headed goddess or a female with cow-like features. Hathor was normally depicted with a pair of horns with the solar disk between them. She was viewed as the symbolic mother of Pharaoh.

In this plague these various gods of Egypt were powerless to protect the cattle and livestock of the Egyptians. Keep in mind that as each plague was sent, the Egyptians probably desperately prayed to their gods to stop the plagues. But in every case their gods were powerless and silent.

The sixth plague—boils

We next come to the plague of boils: “So the Lord said to Moses and Aaron, ‘Take for yourselves handfuls of ashes from a furnace, and let Moses scatter it toward the heavens in the sight of Pharaoh. And it will become fine dust in all the land of Egypt, and it will cause boils that break out in sores on man and beast throughout all the land of Egypt.

“Then they took ashes from the furnace and stood before Pharaoh, and Moses scattered them toward heaven. And they caused boils that break out in sores on man and beast. And the magicians could not stand before Moses because of the boils, for the boils were on the magicians and on all the Egyptians” (Exodus 9:8-11).

The Egyptians worshipped several healing deities, on occasion even sacrificing human beings to them. The victims were burned on an altar, and their ashes were cast into the air, where the wind would blow the ashes over the people. This was viewed as a blessing for them. Moses took ashes from the furnace and threw them into the air. The ashes were scattered by the wind and fell on all the priests, people and the animals that were left. But rather than a blessing, this turned into painful boils—large sores on the people.

This plague would have been an affront to a number of Egyptian gods of healing. One, earlier mentioned, was Imhotep, god of medicine. Another was Thoth, the ibis-headed god of intelligence and medical learning. Another was Nefertem, god of healing. Still another was Isis, another figure in the Egyptian trinity and wife of Osiris. She was supposedly able to bring Osiris back to life after his death, but she was powerless to protect or help the Egyptians from the painful boils that had broken out all over.

Verse 11 pointedly mentions that the magicians suffered from the boils. Priests with their magical powers, especially those in the cult of Sekhmet, yet another goddess of healing besides her major role as war goddess, were the doctors of ancient Egypt. However, the magicians suffered so horribly from the boils that they could barely stand, let alone use the power of their apparently powerless gods to heal others.

The seventh plague—hail

Next came the plague of hail. This would have been very unusual, as the region where this took place receives only about two inches of rain per year.

“Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘Stretch out your hand toward heaven, that there may be hail in all the land of Egypt—on man, on beast, and on every herb of the field, throughout the land of Egypt.’ And Moses stretched out his rod toward heaven; and the Lord sent thunder and hail . . . and the hail struck every herb of the field and broke every tree of the field” (Exodus 9:22-25).

Which Egyptian gods and goddesses did this plague expose as powerless and worthless? Since this plague originated with the sky, the most prominent deity discredited by this plague was Nut, the sky goddess mentioned earlier. She is often depicted in Egyptian art as arching over the earth, her body painted with stars.

But Nut wasn’t the only Egyptian god discredited by this plague. Where was Shu, the god of air and bearer of heaven? Why didn’t he stop this devastating storm? Where was Horus, the hawk-headed third member of the Egyptian trinity and sky god of Upper Egypt? And what of Seth, god of storms and protector of crops? Or Neper, god of grain crops? Or again Osiris, who was ruler of life and vegetation?

This plague was another devastating attack on the country. The Egyptians had already lost fish from their diet when the Nile turned to blood. The plague on the livestock killed off much of it, and animals still in the field at the time of this hailstorm were killed by the hail, so the Egyptians have now lost much of their sources of meat and milk. And still, the various cow deities mentioned earlier could do nothing.

The flax that’s mentioned here was the Egyptians’ major source of fiber for linen clothing. So they lost not only much of their ability to feed themselves, but also their primary material for clothing themselves as well!

The eighth plague—locusts

The plague of hail was followed by a plague of locusts. The plague of hail had wiped out the crops and most plants, but the little that had survived would now be devoured by locusts.

“Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘Stretch out your hand over the land of Egypt for the locusts, that they may come . . . and eat every herb of the land—all that the hail has left.’ So Moses stretched out his rod over the land of Egypt . . . And the locusts went up over all the land of Egypt . . . They covered the face of the whole earth, so that the land was darkened; and they ate every herb of the land and all the fruit of the trees which the hail had left” (Exodus 10:12-15).

History has documented how swarms of locusts have destroyed villages’ food supplies in a matter of minutes. They simply devoured everything that was green—every single leaf and blade of grass.

Again, as with the preceding plagues, the gods of Egypt were silent. You have to wonder what their worshippers thought as they saw the devastation. Where was the jackal-headed guardian of the fields, Anubis? Again, what about the chief agricultural god Osiris? Once more he, Isis, Seth and Neper are all defied—as are Shu, god of the air, and Amun, god of the wind.

The devastated fields battered by hail and burned by fire, now stripped bare by locusts, testified of the impotence of the Egyptian gods.

The ninth plague—darkness

In Exodus 10:21-23 we read about the terrifying plague of darkness: “Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘Stretch out your hand toward heaven, that there may be darkness over the land of Egypt, darkness which may even be felt.’ So Moses stretched out his hand toward heaven, and there was thick darkness in all the land of Egypt three days. They did not see one another; nor did anyone rise from his place for three days. But all the children of Israel had light in their dwellings.”

Imagine the entire world as you know it suddenly going so dark that you can’t see anything. You can’t see other members of your family. You can’t see anything in your house—the table, stools, your bed, your food, the doorway, the windows, your fields, anything. The entire world has gone black. And this darkness is palpable—you can somehow feel it pressing in on you from all around. This goes on for a day and a night. Then another day and a night. Then a third day and night. For people used to bright sunshine 365 days a year, this had to be terrifying!

This plague of darkness was a judgment on Egypt’s religion and entire culture. Of all the gods of Egypt, none were worshipped as much as the sun. The sun god variously known as Re, Ra, Atum or Aten (and sometimes Horus) had become identified with the supreme god Amun, Amon or Amen. Amon-Ra was thus considered the greatest of the gods of Egypt. He was viewed as the creator, the giver of life, who flooded the land with his energizing rays. Many of the pharaohs incorporated his name into their names—names like RAmesses (“drawn forth of Ra”), AMENhotep (“Amen—Amon or Amun—is pleased”) and TutankhAMUN (“living image of Amun”).

But in this darkness Amon-Ra was silent. He was nowhere to be seen, literally. Nothing was visible in the smothering darkness that covered the land. Not only were all of Egypt’s other gods and goddesses powerless, but their greatest and most important god, Amon-Ra, was just as powerless and useless to help them. Again the Egyptians’ gods had failed them.

The tenth plague—death of the firstborn

The 10th plague was very selective. It destroyed the Egyptian firstborn, both human and animal. “Then Moses said, ‘Thus says the Lord: “About midnight I will go out into the midst of Egypt; and all the firstborn in the land of Egypt shall die, from the firstborn of Pharaoh who sits on his throne, even to the firstborn of the female servant who is behind the handmill, and all the firstborn of the animals. Then there shall be a great cry throughout all the land of Egypt, such as was not like it before, nor shall be like it again” (Exodus 11:4-6).

Why the firstborn? God considered Israel His own firstborn among the nations and warned of this retribution on Egypt (Exodus 4:22-23). Also, in that time and culture, the firstborn received the greater share of a father’s inheritance. The firstborn generally became the country’s ruling elite—the generals and military officers, the chief administrators and usually the pharaohs themselves. This particular pharaoh apparently wasn’t a firstborn, since he didn’t die in the plague. Perhaps his older brother had died at a younger age and this pharaoh was next in line. But his son was in line to be the next pharaoh, and he perished in this plague.

Again, the gods of Egypt were silent. Serket, the goddess of protection, was proven powerless. Meshkenet, the goddess who presided at the birth of children, failed to save the firstborn. Sobek, god of protection and fertility who epitomized the might of the pharaohs, couldn’t protect anyone. Renenutet, the god who appeared as a vulture, the special protector god of the pharaoh, could not protect the pharaoh’s son who would be the next pharaoh. And where again was Osiris, the giver and ruler of life?

With this plague, the Egyptian pharaoh finally relented and let the Israelites go. This forcing of Pharaoh to act against his will would demonstrate God’s overthrow of his sovereignty and of the gods who represented it: Hu, the god personifying royal authority; Wadjet, the goddess of royal authority; Maat, goddess of cosmic order under whose aegis the rulers of Egypt governed; and the war goddess Sekhmet, who would supposedly breathe fire against the enemies of the pharaoh.

All these false gods were judged and proven powerless and worthless.

Judgment against Pharaoh

The death of the firstborn was the last plague, but it was not the final judgment on the gods of Egypt. One more major god remained to be further judged and proven to be no god at all.

To continue the story, after the Israelites at last left Egypt, Pharaoh once again changed his mind. He set out with 600 of the best chariots, plus all the other chariots of Egypt—possibly several thousand in all—to return the Israelites to slavery. The Egyptians cornered the Israelites at the sea, but God delayed them by a pillar of fire and cloud while the Israelites crossed through on dry land to the other side.

After the Israelites were across, God lifted the pillar of fire and cloud, and then He brought judgment on the last of Egypt’s major gods. That god was none other than Pharaoh himself.

The pharaohs were considered literal sons of Ra or the divine incarnation of Horus, which meant that they, too, were considered to be gods here on earth. In a way, they were thought to embody all of the gods of Egypt and to be their representative to the Egyptian people. That’s how they wielded so much power over the people—the power of life and death and to enslave. And that’s why they built such great monuments to themselves and such fabulous tombs filled with riches and treasure. These were to honor gods, it was thought, not mere men.

A pharaoh’s greatest responsibility was to keep everything in order—a manifestation of Maat, mentioned earlier—to ensure that the dozens of Egyptian gods and goddesses performed their responsibilities well so the kingdom of Egypt would remain prosperous and strong. But this pharaoh failed spectacularly. He could not withstand the plagues that devastated his kingdom and plunged it into chaos. He couldn’t prevent the death of his own son. And he couldn’t prevent his forces from drowning in the sea. He and his mighty kingdom were left utterly broken and shamed. The last of the great gods of Egypt was tried in the balance, judged and found wanting!

All this considered, we see that the plagues on Egypt were not random. God is a God of logic and order. He sent each of the plagues to specifically show the Egyptians and Israelites that He was greater than all the gods of Egypt.

Taken together, the 10 plagues provided a comprehensive defeat of the pharaoh and of the entire Egyptian pantheon, just as God had promised. This was truly an epic war between the one true God and the demonic forces of darkness. The true God won; Egypt’s gods lost. But why? Such false gods do not really exist, and the false gods deceiving people into believing they do exist are no match for the God of the Bible!

Important lessons for us

So what are some of the lessons we should learn from these events that apply to our lives today?

1. We must realize that God takes sin very seriously.

The severity of the plagues on Egypt shows how seriously God took their sins. Yet it is not just the sin of the Egyptians that God abhors. He hates any sin. We must never minimize the sin in our lives. Any sin is serious, and if we don’t repent of it, it brings eternal death.

2. God is patient, giving us time to repent, but His patience has limits.

And He gives warnings, as He did repeatedly to the Egyptians. But His patience will eventually run out. What follows then is God’s fearsome judgment. May we turn and repent before that happens!

3. Many people “turn to God” in a time of calamity, but when things get better they almost immediately turn away again.

Their hearts are hardened again. We may wonder how Pharaoh could have been so blind and stupid as to harden his heart so many times. But the fact is, Pharaoh wasn’t all that unusual. When the pressure was on, he relented and said he would let the Israelites go. But as soon as the pressure was off, his heart was hardened again.

4. God is trying to get our attention—are we listening?

Remember that the Israelites were victims of the first three plagues along with the Egyptians. God had to shake them up and get their attention so He could begin separating them from the world to make them His chosen nation. The news happening around us now should serve to wake us up. The major trends and events this magazine and its predecessors have foretold for years as revealed in Bible prophecy are beginning to shape up before our eyes.

5. God requires obedience, not just belief.

How were the Israelites spared from the death of the firstborn? Yes they had to trust. And then they had to act. They had to do something. They had to put the blood of the Passover lamb on their doorposts. They had to act and obey in faith, or they would’ve lost their firstborn as the Egyptians did. Likewise, we today have to faithfully act and obey and break away from the Egypt that represents this world so that we might be saved.

6. What are your gods?

The Egyptians had dozens of gods that they worshipped and devoted their lives to. What about you? What do you devote your life to? A false god is anything that comes between you and the one true God. What are the idols that stand between you and God? What consumes your time and energy? Your job or career? Hobbies? Sports? Entertainment? Only you can answer that. Just remember that at some point all these things will vanish away and come to nothing, as happened to the Egyptians, and it will be just you standing there answerable to your Creator for what you devoted your life to.

7. Our all-powerful God is in complete control.

We see this throughout the plagues. God controlled every aspect of it to bring about His purpose of delivering His people from slavery and sin to make a new nation of them. We can take great comfort and hope in that. Nothing is out of His control. He has begun a good work in us and will continue that work in us so long as we are receptive and open to Him and allow Him to continue that work (see Philippians 1:6). Don’t allow anything to come between you and the true God and His will for your life!