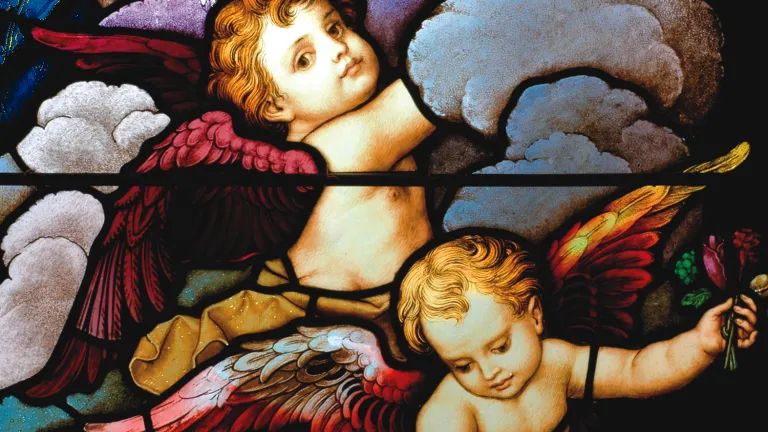

Where Did the Idea of Angels as Babies Originate?

Perhaps one of the oddest depictions of angels is as winged infants, these being referred to as cherubs.

They are nothing like the biblical cherubim—powerful, exotic, four-faced beings (see “Different Kinds of Angels”). And in fact, there are no baby-like angels in all of Scripture.

This figure was known in Renaissance art as the putto, Italian vernacular derived from the Latin word for boy, but its origins go much further back to the Greco-Roman world. “The conception of the putto reaches back in art to the classical world, where winged infants were physical manifestations of invisible essences or spirits called genius, genii, that were believed to influence human lives. Love putti (erote) were familiars of Eros [or Cupid] and Venus. In Bacchanals, which were celebrations of Dionysius (Bacchus), putti represented fertility, abundance, the spirit of the fruit of life and were often depicted in wild revelry” (Lin Vertefeuille, “The Putto—Angels in Art,” 2005, ringlingdocents.org/putto.htm). There were other putti associated with fear, dreams, the god Pan, water sprites, music, etc.

Putti disappeared in the Middle Ages, but reappeared in early Renaissance Italy, used then as personifications of human spirit and emotions (ibid.). They were especially made popular by the artist Donatello, who “gave putto a distinct character by infusing the form with Christian meanings and using it in new contexts such as musician angels” (Wikipedia, “Putto”).

Cupid also came to be represented by the putto figures that had earlier attended to him in Classical art—now representing the presence of love. There was an overlap here with the idea of the cherubim as guardians of God’s glory and pure love, with infants representing innocence and purity (Whitney Hopler, “Cherubs and Cupids: Fictional Angels of Love,” ThoughtCo.com, Jan. 21, 2016). “The irony is that the cherubs of popular art and the cherubs of historical religious texts like the Bible couldn’t be more different creatures” (ibid.).