Archaeology in Line With Scripture

Archaeological finds in the Holy Land continue to shed light on Bible times and corroborate rather than contradict what the Bible says.

Identification of Assyrian siege camp at Lachish and at Jerusalem (June 2024).

Scripture records the invasion of ancient Judah under King Hezekiah by the Assyrian King Sennacherib in 701 B.C.—also attested to in Assyrian inscriptions and artwork. One of the cities conquered was Lachish, south of Jerusalem, famously depicted in the Assyrian wall relief panels on display at the British Museum (see 2 Chronicles 32:9). Sennacherib’s forces then moved on to Jerusalem (2 Kings 18:17).

In studying the Assyrian reliefs, researcher Stephen Compton took note of the placement of the oval-shaped Assyrian siege camp at Lachish. And, as he explains in the June 2024 issue of Near Eastern Archaeology, he matched it to a walled mound just to the north, which an archaeological survey revealed had pottery from the eighth century B.C.—with no occupation before or for centuries after. The site’s Arabic name had been Khirbet [ruins of] al-Mudawwara, a term used in medieval times in reference to the camp of an invading sultan or ruler found in other locations. Some have argued that it just means round place—yet that explanation seems inadequate, as a great many sites are round without such a name. Also, some excavators of Lachish still think the siege camp was to the southwest. Further work needs to be done.

Compton further placed an overlay of his Lachish arrangement over old aerial maps of Jerusalem to find a match for the camp there and found one of almost the exact same size to the north of the city at the oval-shaped Ammunition Hill (named for having been a British ammunition depot during the British Mandate in the 1930s). Its former Arabic name was Jebel [mountain of] el Mudawwara—that same name. He concludes, without an archaeological survey in this case, that this hill was the site of the Assyrian camp. And he further believes it to be the site of Nob, where the priests served at the Mosaic tabernacle at the time of Saul and David, as Isaiah 10:24-32 describes this as the Assyrians’ last stop in coming to attack Jerusalem (though this may be a dual prophecy about the future).

When the British left Israel in 1948, the site was taken over by the Arab forces led by Jordan, who built trenches and fortifications there. In the 1967 Six-Day War the Israelis took it, enabling them to conquer Jerusalem. A monument at Ammunition Hill honors the Israeli soldiers who died fighting to take the site. Thus, the British, Jordanians and Israelis all saw the strategic military significance of this spot for controlling and attacking Jerusalem. Perhaps the Assyrians did too. Yet some believe Sennacherib did not have a camp built—only a blockade. The Bible does mention a camp (2 Kings 19:35; Isaiah 37:36), and Assyrian records mention fortifications—but we don’t have the details.

In any event, the Bible says God kept Sennacherib’s forces from actually attacking Jerusalem and soon destroyed them, as 2 Kings 19 recounts. Assyrian records boast of hemming in Jerusalem but not taking the city.

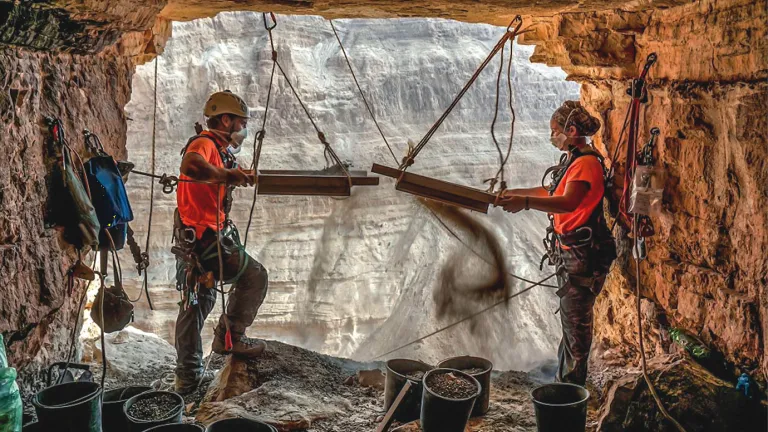

Huge moat found on the north side of the City of David in Jerusalem (July 2024).

Archaeologists have found the remnants of a massive trench, nearly 100 feet wide and 30 feet deep, that cut entirely across the northern part of the spur of land known as the City of David, separating that area from the rise up to the Temple Mount, Mount Moriah. The forming of the structure is dated to at the latest the ninth century B.C., after the city became the capital of David and Solomon and succeeding kings of Judah, but it is likely much older.

The dig team and its directors, Yuval Gadot and Yiftah Shalev, think it’s substantially older—stating that such construction and quarrying are usually dated to about 3,800 years ago. That would have been under the Canaanite people known as the Jebusites. Shalev stated, “If the moat was cut during this period, then it was intended to protect the city from the north—the only weak point of the City of David slope” (as the rest of it was surrounded by deep valleys with walls above them).

This would help explain David’s tactic in conquering the city by, as recorded in Scripture, sending men up through the water system from down near the Gihon Spring low on the eastern slope, with the city high above. Some have wondered why he did not attack the city from the north, passing over Mount Moriah and coming down where it might have been easier to scale the city walls. There had to be some significant barrier or fortification on this side, which archaeologists have been seeking for around 150 years. As 2 Samuel 5:6 says, the Jebusites taunted him when he came, saying the city was so secure that even the blind and the lame could withstand his attack.

And now we find that there was probably a huge moat here at the time preventing assault from the north. Alternatively, it’s possible that David himself had this trench built to protect the north side of his new stronghold—perhaps seeing the need after the Philistines invaded the country following his establishment at Jerusalem. Yet it seems more likely it was already here.

Later, David incorporated Mount Moriah as part of the city in preparation for the temple, which Solomon afterward built. Solomon also built other buildings on the rise up to the Temple Mount called the Ophel. Further, 1 Kings 11:27 says he “closed up the breach of the city of his father David” (New American Standard Bible). It seems unlikely that Solomon or a later king of Judah would have dug the moat to split the enlarged city.

It’s speculated that the moat continued to act as a buffer of sorts even after the northern and southern parts were conjoined—but later between the elite in the Ophel area and the more common city dwellers to the south. Some think there may have been a bridge spanning this buffer or stairs going up and down. It’s clear that the trench was filled in much later near the end of the second century B.C., and then it was eventually forgotten.

2,700-year-old seal in Jerusalem with Assyrian winged genie and biblical names (August 2024).

An exquisite black stone seal with intricate artwork of a winged humanlike figure was recently unearthed in excavations near the Southern Wall of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. Dated to the 600s B.C., it also bears an inscription in Hebrew, Jehoezer the son of Hoshaiah.

An Assyriologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority said that the winged genie or demon is a protective magical figure in Neo-Assyrian art of the period—which has never been found before in Israeli and nearby archaeology. Some have said the writing on the seal is cruder (others say its normal for inscriptions of the time) and conclude that the seal, perhaps used as a stamp and amulet, originally had no inscribed name—that the names were added later after it was acquired. Some think the seal was created locally, while others believe it came from the Assyrians, who had conquered and dominated the region in the years leading up to this time—and the Babylonians who succeeded them adopted many elements from them.

It’s often thought that such would not be found among the people of ancient Judah, but Scripture shows that the nation was corrupted by paganism for much of its existence—with rulers and common people often adopting foreign worship practices. And perhaps some looked at this as merely a royal or noble emblem. No doubt this seal was borne by someone of significant means, perhaps a high official in Judah.

The inscribed names are ones used in the Bible. The name Jehoezer or Yeho-ezer appears in a shortened form as Joezer or Yo-ezer, one of David’s mighty men in 1 Chronicles 12:6. And in Jeremiah 43:2 we find an Azariah son of Hoshaiah, one of the “proud men” who rejected Jeremiah’s words, accusing the prophet of lying. Remarkably, the name Azariah or Ezer-Yahu (“helped has Yhwh”) is essentially the same as Yeho-ezer (“Yhwh has helped”). So this could well be the same person—just as the seals and impressions of other officials named in the Bible have been found.

In any case, the seal gives us particular names in use at the time along with Assyro-Babylonian influence and adoption of pagan culture—just as the Bible lays out.

Apparent shrine next to the Gihon Spring in Jerusalem (January 2025).

Archaeologists in Jerusalem, led by director Eli Shukron, uncovered a row of stone-hewn rooms down on the eastern slope of the City of David near the Gihon Spring, apparently used for religious rituals nearly 3,000 years ago that had been deliberately filled and sealed shut. These contain an oil and winepress, an apparently sacred standing stone and what seems to be an altar with a drainage channel as a site of sacrifices. One room features mysterious V-shaped carvings on the floor, thought to be used for preparing anointing oil or wine or as the base for a loom for special garments or a tripod structure for dealing with sacrifices.

Researchers have said this apparent temple was most likely built at the latest at the end of the Middle Bronze Age (around 1550 B.C.) and went out of use in the late 700s B.C. at the time of righteous King Hezekiah. A small cave was carved into the hill behind where a stash of objects from the 700s was found—cooking pots, jars with fragments of Hebrew writing, loom weights, scarabs, stamp seals and grinding stones. The careful sealing of this cave before the building went out of use may suggest it was a favissa, or cultic storage place.

Numerous sources reporting on this discovery declared it shocking to find what they call a second or competing temple in Jerusalem—against the biblical impression of Solomon’s temple as the sole place of worship. But these are misinformed as to what the Bible actually says.

First of all, we should be skeptical when archaeologists say they have found a cultic site because that can be somewhat imaginative without finding written proof. Still, there do appear to be some ritual aspects to this place located near a significant site in the city, the water source of Gihon.

It’s been argued that this facility dates from the Canaanite Jebusite period, but one would wonder why it would have been retained by King David if it originated in pagan worship. Some say it dates back to the time of the priest-king Melchizedek, whom Abraham encountered at Salem (Jerusalem) in Genesis 14. (To learn more about this figure, see the sidebar in our free study guide Who Is God?) That’s possible, and maybe there was a continuing tradition into David’s time. There’s no way to really know.

Or perhaps it did not start out a ritual site but became one at the time of David’s reign. Some have argued that Solomon’s temple was over the Gihon Spring, but that’s false. Yet something else may have been here in David’s time. Archaeologist Scott Stripling and others think this may be where David set up a tabernacle or tent for the Ark of the Covenant when he brought it to Jerusalem (2 Samuel 6:17; 1 Chronicles 15:1; 2 Chronicles1:4)—perhaps erected over parts of the stone room divisions, especially as Stripling has found that the Mosaic tabernacle at Shiloh was evidently set up over some stone room platforming there.

David actually had priests serving in two places—at the Mosaic tabernacle as well as the tent at Jerusalem. Just where was this tent?

We should also consider that David sent Solomon to the Gihon Spring for his coronation (1 Kings 1:32-39). Why? Perhaps this is where the ark was. Interestingly, we later find his descendant Joash crowned by a pillar stone (2 Kings 11:14). Maybe this happened in the same place. (Josiah was also crowned by a pillar stone in 2 Kings 23:3.)

Or it could be that this was just a Canaanite pagan site that David closed off but later apostatizing kings put back into use. Or it could have been the sacred site of the ark before the ark was put in Solomon’s temple as well as the place of coronation—with this sacred site later corrupted into a pagan shrine. Even Solomon himself ended up building temples to pagan gods around Jerusalem (1 Kings 11:4-8). Under the rule of his son Rehoboam the false worship at high places continued (1 Kings 14:22-23), and we find this through Judah’s history again and again.

It’s interesting that the newly discovered site came to an end at the time of Hezekiah. For he not only removed the high places and destroyed pagan iconography, but he even destroyed holy objects that had become corrupted. The bronze serpent that Moses had fashioned at God’s direction had become an object of false worship for people, so Hezekiah broke it in pieces (2 Kings 18:3-5).

Eli Shukron sees the filling in of the site as part of Hezekiah’s reforms, stating, “The Bible describes how, during the First Temple period, additional ritual sites operated outside the Temple, and two kings of Judah—Hezekiah and Josiah—implemented reforms to eliminate these sites.”

This is refreshing to see since many recent scholars tout evidence of idolatrous worship in Israel and Judah as somehow contradictory of the Bible—when that’s exactly what the Bible repeatedly laments and rebukes. But thankfully a few ancient kings like Hezekiah and Josiah boldly took a stand for God. And we may well have evidence of that right here in this new find.

Evidence of Necho’s Egyptian army victory over Josiah at Megiddo (March 2025).

The Bible says that King Josiah of Judah, in his process of righteous reforms, extended his control to former territories of Israel in the north. Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II, an ally of the Assyrians, marched north to fight with them against the ascendant Babylonians, passing through the northern Israelite territory. Josiah and his forces came out to repel this ingress, to which Necho replied that God had sent him on this mission and that Josiah should not stand in his way. Nevertheless, Josiah went to battle against the Egyptians at the valley or plain around Megiddo, was wounded and died from his wounds (2 Kings 23:29-30; 2 Chronicles 35:20-24). Egypt was then briefly in control of the country until losing to the Babylonians in the north—whereupon the Babylonians took control of the land.

Past Megiddo excavations had turned up no structure that could be conclusively dated to this time of Egypt’s victory over Josiah in 609 B.C. But three seasons of digging in the northwestern sector over the years 2016 to 2022 yielded the looked-for results, which were recently published. Remains of a new building were found in a layer correlating to the time of Josiah. And in this building was found the largest collection of Egyptian pottery ever discovered in the region. This pottery was of low quality—fitting not fine tableware of trade but, as pointed out by the excavation directors, a stream of supplies, most likely for Necho’s army. They think the building was part of an Egyptian administrative center with a garrison—which would well match this time.

Also found were many examples of Greek pottery—which fits with the Egyptian army using many Greek mercenaries. And there was a fragment of a jug made of clay nearly exclusive to Jerusalem—showing a Jewish presence here in the north of the country at Josiah’s time.

Once again, the Bible is shown to be a trustworthy record of history.

AI dates Dead Sea Scrolls earlier than thought, including Daniel (June 2025).

One of the greatest finds from antiquity in modern times was the discovery of the famous Dead Sea Scrolls, a major trove of ancient manuscripts and fragments buried in the Judean desert, including portions of nearly all the books of the Hebrew Bible at such an early date. Most of the items found have been dated to between the second century B.C. and second century A.D.—based on laborious paleographic analysis, examining the development of writing styles with few clear time markers. Now a new approach is yielding even older dates for many of the scrolls.

The team behind a paper in the scientific journal PLOS One, titled “Dating Ancient Manuscripts Using Radiocarbon and AI Based Writing Style Analysis,” trained Enoch, an AI-based prediction model, with writings on carbon-dated parchment samples, teaching it to recognize even microscopic ink trace patterns to more accurately assess writing developments across the period in question to establish date-range markers. While many scrolls showed the same time frame earlier determined, others were assigned much earlier dates than before. While all the scrolls date long after the original biblical writing and compilation, earlier dating means these are less removed in time from the initial manuscripts—and they demonstrate great consistency in passing down what’s recorded.

This process has yielded very interesting implications for the book of Daniel. Many have concluded its composition was after the time of the Maccabees in the late 160s B.C.—to explain away its complex prophecies in chapter 11 as having been fraudulently manufactured after events transpired. Yet researchers were surprised to see the Dead Sea Scrolls’ copy of the book dated to a range of 220 to 165 B.C., meaning it was probably from well before the time of the Maccabees—and indeed the book of Daniel itself is from three centuries earlier.

Again and again, the Bible is validated as an authentic record—not just of history but even advance prophecies that were genuinely fulfilled in subsequent events.