Paganism In Christianity

Many aspects of traditional Christianity - holidays, practices and doctrines - came not from Christ or the Bible but from ancient pagan religion.

The traditional holidays with their annual rituals are coming: Halloween costumes, Christmas decorations, Easter bunnies. Where did those traditions and practices come from? Celebrated as Christian holidays, shouldn't these occasions be faithful to what the Bible says?

Halloween

Jack-o-lanterns have been around for centuries as part of an ancient Celtic celebration at the start of the winter season. The Druids (a sort of pagan priesthood) believed that at this time of year the barriers between our world and the supernatural weakened and broke down. Expecting the souls of the dead to roam the land, they built large bonfires to frighten them off and slaughtered animals—or even people—to appease the evil spirits. The jack-o-lantern represents a poor soul caught between the two worlds, and some believe it served as a warning meant to ward off bad spirits. Incidentally, pumpkins are not common in Europe, so the original jack-o-lanterns were carved from turnips (The Encyclopedia of Religion, 1987, p. 176, "Halloween").

Why is much of modern Christian ritual and belief based on pagan practice rather than the Bible? Isn’t it enough that people honor God however they want?

Carved vegetables, talismans against evil spirits, human sacrifice—these are not in line with the teachings of Jesus Christ. Halloween is still looked to by some as All Hallows' Eve—the night before the Catholic All Saints' Day, a supposedly holy occasion. Yet with all its ties to the occult and dark forces, Halloween is anything but holy. And it's now shunned by many professing Christians. They see no value in celebrating a holiday that clearly originated from polytheism (the worship of multiple gods) and animism (belief in spiritual forces in inanimate objects). Such religions have been broadly referred to as pagan in Western societies since the time of the late Roman Empire.

If most of the beliefs and practices associated with Halloween originated in paganism, does the pagan influence end there?

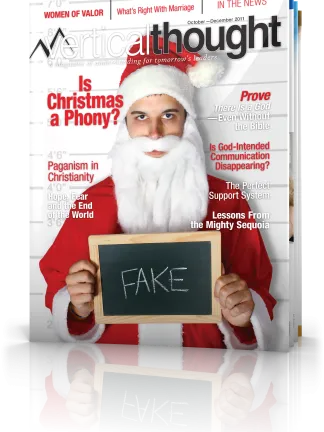

Christmas

The Druids in ancient France and Britain staged a 12-day festival at the time of the winter solstice. They believed it was the high point of an annual battle between an ice giant, representing death, and the sun god, representing life. They built large bonfires to cheer on and assist their champion, the sun. The Druids and other pagan leaders knew, as we do today, that the days always get longer as the calendar progresses through winter toward spring regardless of their seasonal rituals—but still they persisted in them (L.W. Cowie and John Selwyn Gummer, The Christian Calendar, 1974, p. 22). Unfortunately, so does much of Christianity today.

What is today thought to be a celebration of the birth of Christ began as the pagan midwinter festival. One unbiblical tradition of this holiday is the use of greenery. Decorating with green plants in late December through the beginning of January was one of the ways Druids "honored and encouraged" the sun god at the time of the winter solstice. Families commonly cut down an evergreen tree to bring into their home, where they decorated and displayed it in a prominent place. In the Middle Ages, this ritual of paganism persisted and was eventually adapted and given a Christian label, as Roman Catholic missionaries worked to convince people to worship the Son of God rather than the sun god. In due course, German immigrants brought the practice of decorating evergreen trees to America, where it has flourished. As you may have already guessed, the "Twelve Days of Christmas" of the famous carol owe their origin to the pagan festival too (ibid.). (For more on the pagan origins of this holiday, see "Is Christmas Phony?".)

Easter

Even Easter, which many assume was instituted to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus, is steeped in connections to paganism. The name "Easter" ultimately derives from the name of an ancient Chaldean goddess Astarte, who was known as the "Queen of Heaven." Her Babylonian name was "Ishtar." Since most languages pronounce "I" as ee, it's not hard to see how eesh-tar and its linguistic variants could eventually become Easter (see Vine's Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words, 1985, New Testament Section, p. 192, "Easter").

As the goddess of love and fertility, Ishtar's symbols were—you guessed it—eggs and rabbits! Rabbits can bear several litters of young each year and thus were highly fertile animals familiar to these ancient people. Worshipping Ishtar during an annual spring festival was intended to ask her blessing of fertility on the crops being planted at that time of year. Decorating eggs as a means of worship seems harmless until you consider that the people also practiced ritual sex acts, often with temple prostitutes, to honor the goddess (Nelson's New Illustrated Bible Dictionary, p. 509, "Gods, Pagan"). That doesn't sound very Christian, yet most Christians continue to associate eggs and bunnies with what they think is the most solemn holiday of the year.

Traditional Christian doctrines

Unfortunately, some of the most basic things believed by most professing Christians derive from ancient paganism rather than from the Bible. The idea that people have immortal souls was first taught in ancient Egypt and Babylon. The Greeks likewise taught that at death the soul would separate from the physical body (Jewish Encyclopedia, 1941, Vol. 6, pp. 564, 566, "Immortality of the Soul"). That idea was merged into Christianity from Greek philosophy. It did not come from inspired Scripture.

The ancient Egyptians developed the concept of going to heaven. In their mythology, the god Osiris was killed but then raised back to life, whereupon he went to a distant heavenly realm. The Egyptians concluded that if he could do this, then human beings could follow (Lewis Browne, This Believing World, pp. 83-84). This heavenly reward was a central teaching of several ancient mystery religions—but not the religion of the Hebrews or early Christians.

Even some Christian teachings about Jesus have origins in paganism rather than the Biblical record. Babylonian mythology regarding Ishtar claimed that she had a son named Tammuz. He died each year, but then would be reborn again in the spring. The Babylonian veneration of both the mother and child influenced later versions of Christianity that deified Jesus' mother Mary as much as Jesus Himself (Sir James Frazer, The Golden Bough, 1993, p. 326). This stands in contrast to Scripture, which honors Mary, but reveres no ordinary human being—only Christ.

The Chaldean symbol for Tammuz was the letter tau, which appears as a san-serif "t" and is commonly considered a cross (Babylonian Mystery Religion, p. 51; Vine's, "Cross, Crucify"). While the Bible does indeed teach that Jesus was crucified, there is no record of the shape of the crucifix. At that time, Romans used various forms of upright stakes, some with crossbeams and some without. The Bible gives no indication that the early Church ever used the cross as a religious symbol, but several pagan religions had been doing so for centuries before Christ was born.

How to worship God

Why is much of modern Christian ritual and belief based on ancient pagan practice rather than the Bible? Isn't it enough that people honor God however they want? Human logic might say that one can do anything to show personal religious faith as long as the intent is to worship God. However, God has a much different view.

When He gave the ancient Hebrews instructions about how to worship Him, God also told them very specifically not to borrow or copy the practices of pagan cultures around them. He said, "Do not inquire after their gods, saying, ‘How did these nations serve their gods? I will also do likewise.' You shall not worship the Lord your God in that way" (Deuteronomy 12:30-31). The point of faithfulness is that God defines how He should be worshipped, not man: "Whatever I command you, be careful to observe it; you shall not add to it nor take away from it" (Deuteronomy 12:32).

Jesus offered a challenge for us all: "But the hour is coming, and now is, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth; for the Father is seeking such to worship Him" (John 4:23). We live in a world historically deceived about the truth—especially religious truth. But when you do learn the truth, take Christ's challenge: believe it and follow it. God is seeking you.